In the late 1980’s many interoperability problems, among systems and other similar issues, became very apparent while dealing with large architectures at the Department of Defense. According to (Global Security, 2010) soldiers had to use pay phones and other electronic devices from home to communicate with the Pentagon, due to the inability of several systems to interchange communications and/or data.

The 1991 Gulf War highlighted more difficulties of interoperability when our Armed Forces could not find the SCUDs and many systems still did not fully work together as planned (PBS, 2010).

The need for a framework to help the decision making process became urgent. To accomplish this, the Architecture Working Group (AWG) was created. This team was comprised of representatives from every command, service, and agency across the Department of Defense. The C4ISR (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) Architecture Framework 1.0 was the initial product of this working group (Dam, 2015).

After this first release the working group received thousands of comments and corrections from many sources. As a result of that and other circumstances like the Y2K problem, during the next years the framework evolved originating the DoDAF V2.02 on 2012.

The DoDAF has been especially formulated to address the Department of Defense six cores (Ertaul & Hao, 2009):

- Joint Capability Integration and Development System (JCIDS); to ensure the capabilities needed for war missions are identified and met. If gaps between required and actual capabilities are identified, measures must be taken to fill them.

- Defense Acquisition Systems (DAS); to manage investments as a whole.

- System Engineering (SE); balance system performance with total cost ensuring developed systems match capability requirements.

- Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE); plays important role from the initial capability requirement analysis to decision making for future programs.

- Portfolio Management (PfM); it deals primarily with Information Technology investments. It is meant to maximize return on investments while reducing risks.

- Operations; define the activities and their inter-connections supporting the military and business operations carried out by the DoD.

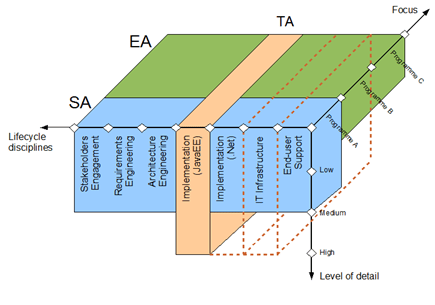

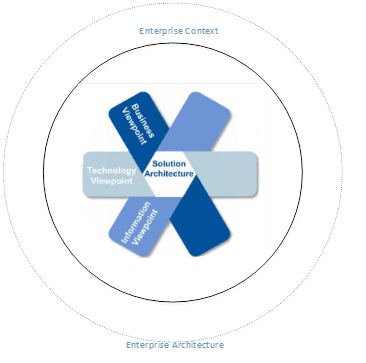

It considers these basic concepts:

- Models: useful for the visualization of architectural data. They could be documents, spreadsheets, dashboards or other graphical representations. Serve as templates for organizing and displaying data.

- Views: data collected and presented in a model.

- Viewpoints: organized collection of views, usually representing processes, systems, standards, etc.

The framework acknowledges eight viewpoints as following (Dam, 2015):

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between models, views and viewpoints.

DoDAF provides a six-step process for developing architectures. This is not a detailed architecture development process; instead, it is an overview (Dam, 2015). The framework is missing a detailed methodology. Usually TOGAF is used to complement this framework.

As the field of EA grows, more corporations are starting to use EA to gain competitive advantage and to be able to adapt themselves to the continuous changes in the business environment and technology. To develop the architectural vision of any organization, a single framework usually is not enough, knowing or getting familiar with multiple frameworks become very helpful. Change is constant and the EA frameworks must evolve as environments transform.

References

Dam, S. H. (2015). DoD Architecture Framework 2.0. Manassas, VA 20109: SPEC Innovations.

Ertaul, L., & Hao, J. (2009). Enteprise Security Planning with Department of Defense Architecture Framework (DODAF). Hyaward, California.

Global Security. (2010). Operation Urgent Fury. Retrieved from GlobalSecurity.org: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/urgent_fury.htm

PBS. (2010, August). FRONTLINE. Retrieved from pbs.org: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/gulf/weapons/scud.html